Gustav Mahler – Symphony No.2 (Genesis & Movement I)

n

n

Genesis

n

In 1888, when Gustav Mahler began working on the first and second movements of his Second Symphony, he had completely immersed himself in paradoxical thoughts regarding death and mortality. Attempting to follow on from a narrative that figuratively and literally hit a dead end (the death and burial of the hero of his First Symphony), Mahler faced an uphill battle with the sketches for the Second Symphony. Between 1888-94, Mahler had made many decisions as to what the Second would represent both musically and programmatically.

n

Now lovingly referred to as ‘The Resurrection Symphony’, this work was a labour of love for Mahler, as it took him around six years to complete. Alongside writing the Second Symphony, Mahler was also setting music to the poems of Des Knaben Wunderhorn (‘The Youth’s Magic Horn’). Literary and artistic sources were used throughout the compositional process of the symphony, and these will be highlighted in subsequent blogs in this series.

n

n

Movement I

n

In the beginning, Mahler wrote extensive and detailed programme notes for the Second Symphony, even though the order of the movements was always in question. The structure we know today sees five movements, all of which were composed very much independently from each other.

n

The first movement of the Second Symphony, subsequently entitled Todtenfeier (‘Funeral Rites’), was composed as a tone poem before Mahler decided to use it within the symphony. Although composed six years before the completion of the work, and wasn’t initially intended to be used in the symphony, this movement offers an unlikely programmatic link to the end of his First Symphony. He explained this to Max Marschalk in a letter:

n

n

“I called the first movement ‘Todtenfeier.’ It may interest you to know that it is the hero of my D major symphony that I bear to his grave, and whose life I reflect, from a higher vantage point, in a clear mirror. Here too the question is asked: What did you live for? Why did you suffer? Is it all only a vast terrifying joke? We have to answer these questions somehow if we are to go on living – indeed, even if we are only to go on dying! The person in whose life this call has resounded even if it was only once, must give an answer. And it is this answer I give in the last movement.”

n

n

Although the original programme notes were not carried through the many revisions of the symphony, the manuscripts are still useful to gauge an idea of the programmatic context of the symphony. Here is the translated note for the first movement:

n

n

“We stand by the coffin of a well-loved person. His life, struggles, passions and aspirations once more, for the last time, before our mind’s eye. And now in this moment of gravity and of emotion which convulses our deepest being, when we lay aside like a covering, everything that from day to day perplexes us and drags us down, our heart is gripped by a dreadfully serious voice which always passes us by in the deafening bustle of daily life: What now? What is this life and this death? Do we have an existence beyond it? Is all this only a confused dream, or do life and this death have a meaning? And we must answer this questions if we are to live on.”

n

n

Between 1888-1901, Mahler revised the programme and the orchestrations for the first movement 4-5 times (See Example 1). During this period, Mahler lost his mother, father and sisters, so the changes may have reflected the mental state that Mahler was in at that point in time. It certainly wasn’t unusual for Mahler to project his inner programme within his music. Throughout even just the opening movement, we hear and feel emotions of anger, despair, and vulnerability. The progression of his emotional experiences with grief and loss are so tightly woven throughout this symphony, that even though he took the written programme away from audiences from 1901, one can still experience the full ‘Mahler effect.’

n

n

| Date | Action |

| August/September 1888 | First copy of the first movement |

| February 1889 | Death of Bernhard Mahler |

| 1889 | Death of Marie Mahler and Leopoldine Mahler |

| 1891 | Change of title from “Symphonie in C Moll/I. Satz” to “I. Satz, ‘Todtenfeier’ |

| April 1894 | Revisions made on both the music and the programme of Todtenfeier |

| January 1896 | Bauer-Lechner’s first draft of the programme |

| March 1896 | Letter to Max Marschalk outlining the Todtenfeier programme (with a lot more detail and reference to the big eschatological questions) |

| December 1901 | Dresden programme written (again this version is much longer and more developed than the previous copies) |

n

n

Example 1 – The timeline of Todtenfeier

n

n

The piercing opening tremolo from the upper strings paves the way for the regimented semiquaver motif that is established by the cellos and basses. As new themes emerge, they begin to tangle together to create a complex section built on counterpoint. Music critic, Ferdinand Pfohl, described the opening from the 1895 Hamburg performance “as though the presentiment of something horrid burst into the soul of a man, which rapidly seized his entire feeling and made icy shudders ripple through his limbs.”

n

Mahler creates a lot of effective light and shade within this movement, however there is always a sinister undertone threaded throughout the music. His use of chromatic harmonies, angular melodic lines and extreme dynamics all play into this dramatic and theatrical movement. The brass section are often the leaders of these extreme dynamics, and this can be first heard in the ‘death fanfare’, which really packs a punch!

n

Alongside these loud and dramatic sections are much more peaceful, dreamlike motifs. This is where the significance of the First Symphony’s programme comes into play. These sections reflect the happier memories of the young hero from the First. Unlike the First, the Second’s dream motifs always descend back into anguish and disarray, that always reminds the listener that the story has moved on.

n

Mahler poses a number of huge questions within this symphony and the turmoil of trying to answer these questions can be heard throughout sections of the music. One key moment is where a huge climax is built throughout the orchestra which sees the strings play col legno (meaning to play with the wood of the bow, rather than the hair), and the brass proclaiming the thrilling fanfare. This leads to a ‘plunging motif’, where the entire orchestra descends quickly with chromatic triplets. Some have said this represents the fall from reality into the depths of hell. The climax here continues, and the brass lead with a fanfare that Mahler stretches by using a mix of triplet quavers, straight quavers and semiquaver rests. This leads to the final bar which sounds like the end of the movement. Out of nowhere, the lower strings return with their regimented opening theme.

n

There are not many instances throughout the entire symphony where the orchestra play in unison, but the two in the first movement are both plunging motifs. The last few bars of this first movement sees the orchestra unite once more to plunge into hell, before the music fades out (See Example 2).

n

n

n

Example 2 – The last plunging motif which ends the first movement (b. 437-445)

n

n

Mahler uses fragments of music to foreshadow the Last Judgement in the final movement. The horns play a theme based on the Dies Irae (Day of Wrath), as well as hinting to the ‘Resurrection Theme’ heard in the finale. There is some circumstantial evidence to suggest that there were initially allusions to Goethe’s poem Meeresstille. The key verse being:

n

n

Todesstille fürchterlich! / Terrible silence of death!

n

In der ungehuren Weite / In the dreadful vastness

n

Reget keine sich. / Not a wave is moving.

n

n

It is certainly possible that Mahler used Goethe’s poem as an overriding metaphor for Todesstille (‘Silence of Death’), which suggests that Mahler may have used this in conjunction with the more pastoral sections in the movement. The impression that is left at the end of the first movement reflects Mahler’s want to artistically express many different perceptions of death and the afterlife. By analysing parts of the score against Mahler’s literary sources and programmes, it paints a vivid picture of what the symphony is trying to communicate.

n

This opening movement lays the foundation for the rest of the symphony, thus Todtenfeier is only the beginning of this journey through life, death and the afterlife.

n

n

Ⓒ Alex Burns

n

n

I gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the Gustav Mahler Society UK for this Mahler 2 blog series.

n

To learn more about the fascinating life and music of Gustav Mahler and to enjoy study days, social events and recitals which are held throughout the year, enquire about membership at: info@mahlersociety.org or visit the Gustav Mahler Society UK website.

n

n

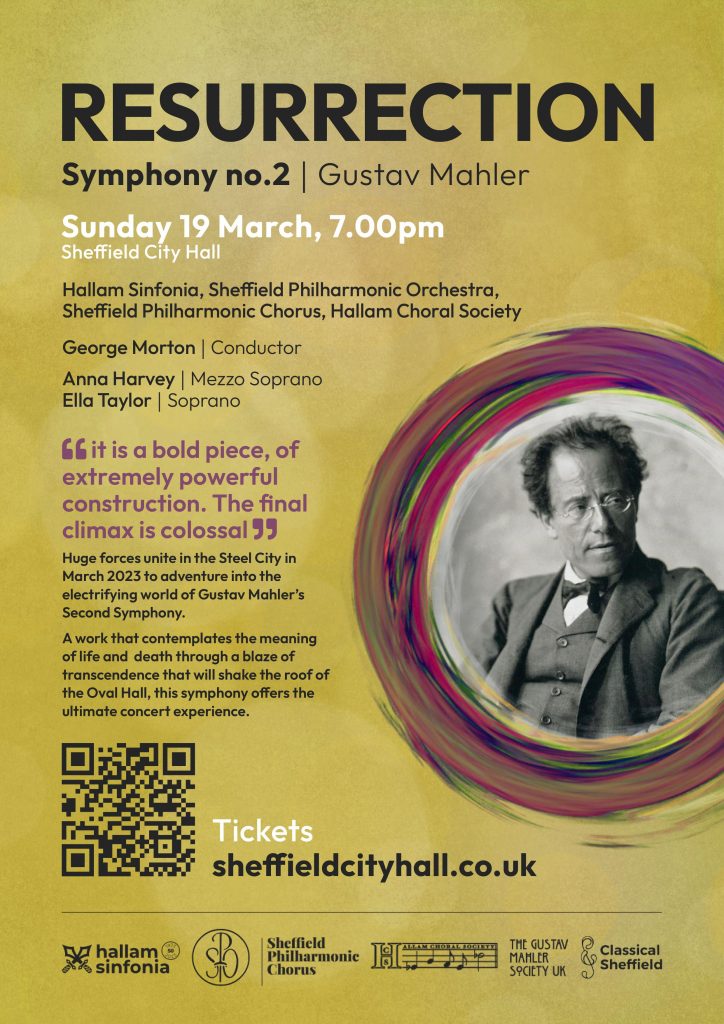

You can experience this epic symphony for yourself this March in Sheffield when over 300 local musicians unite to perform this incredible work.

n

n

n

The post Gustav Mahler: Symphony No.2 – Genesis & Movement I appeared first on Classicalexburns.

n